Tapiche's First Scientific Paper Published!

Tapiche's First Scientific Paper Published!

Update: April 12, 2021

At the height of turtle nesting season this past July 2020, parts of our turtle hatchery were attacked by ants. The hatchery was divided into four boxes this year, and at the time when we first noticed the ant attacks, the turtles in the first two boxes had already hatched. Though we did find a few ants in those first two boxes, it didn't strike us as alarming or worth noting. Half of the third box hatched successfully, but in the second half we noticed that some nests were full of ants. Baby turtles that were in the process of emerging from the eggshells as well as those climbing out of the nest were being actively attacked by ants, some still having the ants biting into them when we lifted them out of the sand. Some eggs with hatchlings inside were so severely attacked that the hatchlings died before they hatched, never making their way out of the eggshells. The turtles we found with ants biting into them seemed weak and somewhat paralyzed, some having wounds over the soft flesh of their heads and legs.

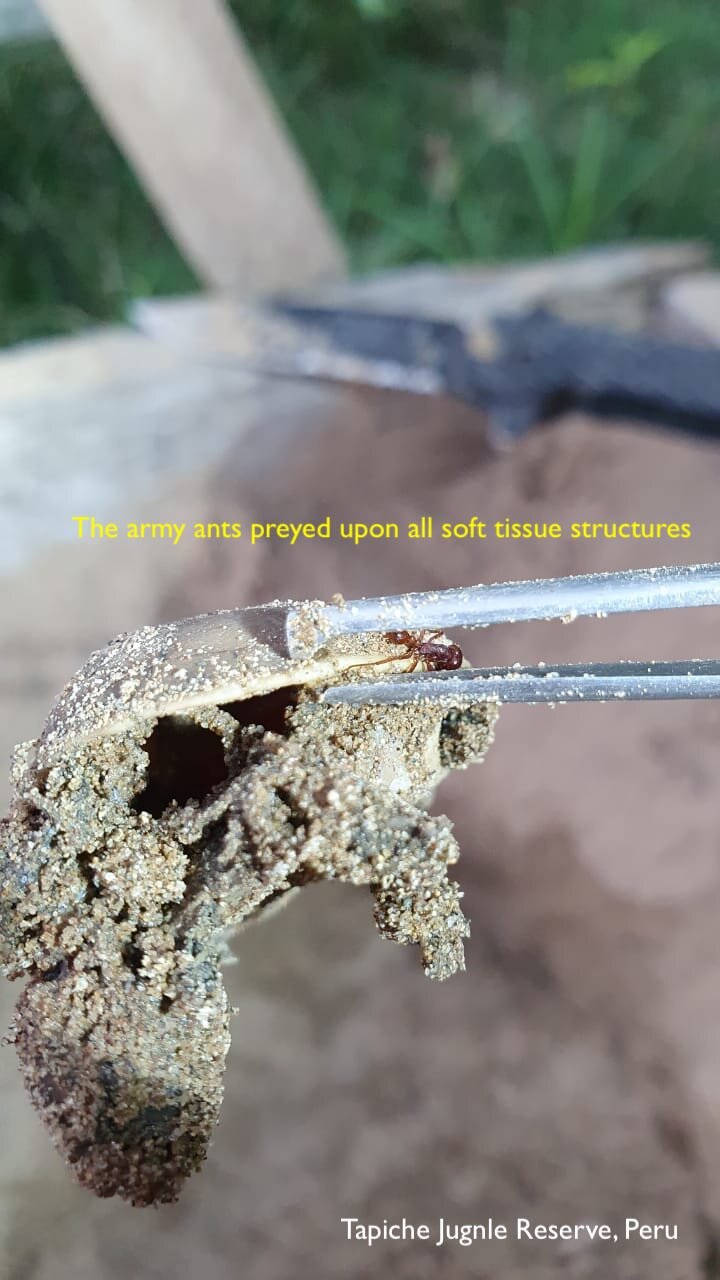

We took photos to document this and sent them on to our dear friend and supporter Sean O'Donnell PhD, expert in social insects and professor of Biodiversity, Earth & Environmental Science and Biology at Drexel Uniersity in the USA. He identified the ants as army ants (Labidus coecus), and we started documenting more of the ant attacks with photos and videos.

When we checked on the nests of the fourth box, we saw a shocking and sad picture: all of the nests in that box were so severely attacked by the ants that the babies died inside the shell, and none of those turtles could hatch. The nests were still full of ants, and the eggs had holes in them, presumably from the ants chewing through the shells. The dead hatchlings inside the shells had wounds all over their bodies. We lost 1000 turtle eggs to this ant attack.

This immense loss felt quite tragic and sad, not just for the number of baby turtle lives involved but also due to the tremendous amount of work necessary to rescue and incubate those eggs. From this adversity, though, came the first scientific paper published about Tapiche! Sean led us through the process of documenting and reporting these ant attacks, and our paper, "Predation on nests of three species of Amazon River turtles (Podocnemis) by underground-foraging army ants (Labidus coecus)" was published on 10 April 2021 in Insectes Sociaux (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-021-00814-8).

Some of the questions this experience prompted us to ask were, of course, ways in which we could improve incubation conditions to prevent a repeat of this type of attack in the future. The hatchery is built above ground, using soil and nesting materials brought from the beaches where the nests are found. It would be difficult to completely insulate the incubation boxes from infiltration underneath; the ants are expert subterranean navigators, their small size allows them to pass through even very small crevices, and it appears that they may be able to chew through protective barriers.

All of the conditions within the incubation boxes were replicated as closely as possible to the nests where the eggs were originally found, including the building material, the shape and construction of the nests, the depth of the nests in the ground, and the spacing between each nest. While it's possible that the high density of eggs in a concentrated area may have been an easy target that lured the ants to the hatchery, we've never had problems with this in the past even with thousands of eggs in the hatchery. The nests we find on the beaches are often closely clustered, sometimes almost overlapping, and turtles have been seen reusing the exact same spot where a previous nest had been made, which means whatever organic scent or trace of these nests remains in the same area over the years and flood cycles. This would present a similarly dense concentration of eggs within a small area as we have in the hatchery.

It's hard to say what the turtle density in our area would be today if their population had not been so negatively impacted by humans. Poaching in the region was rampant before the reserve was established, so we never got a "before" picture of a "healthy" local turtle population.

Setbacks like these are frustrating, but there are always many unpredictable factors when working with nature. The best we can do is continue to learn and improve over time and with each lesson. We are so thankful to Sean for making the publication possible, and we thank all of our supporters out there for helping us through these challenges!